Extracted from ’Memorials of the Royal Yacht Squadron’ by Montague Guest (Librarian of the RYS) and William B Boulton, printed in London in 1902.

In 1859 was agitated the famous grievance of the supposed privileged possessed by the [Royal Yacht] Squadron of flying the White Ensign. A debate in Parliament and the publication of a Blue Book were necessary to compose the agitation of the group of the aggrieved ones in this matter. It was really, in essence, a very simple one, which had been somewhat complicated by the blundering of a clerk at the Admiralty, and the privilege as a fact was no privilege at all. As some misconception of the matter still exists, it may perhaps be well but it’s history should here be plainly stated.

Royal Yacht Squadron White Ensign

….the vessels of the Squadron were by successive concessions of foreign governments granted privileges of exemption from port dues in foreign harbours, which placed them as pleasure vessels in a class apart from merchant vessels. [Briefly, this was because Squadron yachts, many of them armed and often with royalty or the ‘great and good’ on board, frequently visited foreign ports together with the British fleet. It was for this reason also that King William IV decreed in 1833 that the ‘Club’ should be called the ‘Squadron’.] These privileges in fact set them on the same footing as the King’s ships and it was felt by the Admiralty that a distinguishing ensign for these vessels was necessary for the convenience of the officials of the foreign Governments whose harbours they visited. There were only three ensigns available for the purpose – the Red, the White, and Blue. Of these the Red was already allocated to merchantmen, the White was worn then, as now, by the King’s ships, and the Blue by another class of vessel under the Admiralty – transports and the like. The privileges granted by foreign Governments to yachts being exactly those enjoyed by the King’s ships, it no doubt occurred to the Admiralty that the same ensign would be most suitable as a distinguishing flag for the pleasure vessels. In any case, as we have seen, permission to wear the White or St George’s Ensign was given to the Squadron by a warrant of the Admiralty in the year 1829.

It is important to note that the wearing of the ensign was not confined to the yachts of the Squadron but was permitted by those of any other recognised yacht clubs who chose to apply for it. Most of the clubs existing at the time availed themselves of the permission – the Royal Thames, the Royal Eastern, and the Royal Western Yacht Clubs, among others. Shortly after 1829 the Irish members of the Royal Western Yacht Club seceded and formed a club of their own entitled the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club. This club was granted the use of the White Ensign in 1832 in circumstances which show how little the flag was valued at the time, and that its use was not regarded in any way as a privilege. Mr O’Connell, the original Commodore of that club, addressed a letter to the Admiralty dated the 30th January, 1832 which contain the following passage:-

“A White Ensign has been granted to the Royal Yacht Club, a Red Ensign to the Royal Cork, a Blue Ensign to the Royal Northern, and as the only unoccupied national flag, we have assumed the Green Ensign.”

To this the Secretary of the Admiralty replied:-

“I am commanded by my Lords Commissioners to acquaint you that you may have as a flag for this club either a Red, White or Blue Ensign with such device thereon as you may point out, but their lordships cannot sanction the introduction of a new colour to be worn by British ships.”

The Irish club then chose the White Ensign, not considering it as any privilege, as is evident from Mr. O’Connell’s letter, but rather the reverse, and they added a crown, and a very small wreath of pale shamrock leaves as a distinguishing mark. So, the matter rested for ten years.

Meanwhile as the number of yacht clubs and of private vessels increased there were constant complaints reaching the Admiralty through the Foreign Office of irregularities committed in foreign ports by owners of pleasure vessels flying the White Ensign. There were charges of smuggling, of evasions of quarantine regulations, of landing and embarking passengers, and of a general abuse of the privileges which the flag conferred in foreign ports – privileges which had been granted to yachtsman entirely by the efforts of the Royal Yacht Squadron in the early days. There was a continual correspondence between the Admiralty and the secretary of the Squadron on the subject during those ten years which is preserved at the Castle [clubhouse of the RYS in Cowes on the Isle of Wight], and goes to show that a great part of that gentleman’s time was spent explaining that such and such a vessel which had committed such and such an outrage at Lisbon or Marseilles or Naples had no connection with the club. These irregularities had the natural result of bringing odium upon other yachtsmen flying the same ensign and who were innocent of any abuse of its privilege, and the nuisance at last became so injurious to the reputation of the Squadron that a meeting of the club in 1842 passed the following resolution:-

“The meeting requested the Earl of Yarborough to solicit the Admiralty to alter the present colours of the Royal Yacht Squadron, or permission to wear the Blue Ensign, etc, in addition, in consequence of so many yacht clubs and private yachts wearing colours similar to those at present worn by the Royal Yacht Squadron.”

There followed a correspondence between Lord Yarborough and the Admiralty in which the former made complete of, “the many irregularities committed by persons falsely representing themselves as members and bringing undeserved disgrace on the Royal Yacht Squadron.” The result of the correspondence appears in a letter from Mr. Sidney Herbert to the Secretary of the Squadron dated from the Admiralty on July 22nd, 1842. The Admiralty refused permission to the Squadron to change their flag and decided to confine the use of the White Ensign to its members. “ I am commanded by my Lords,” wrote Mr. Herbert, “to inform you that they have consented to much of the above request as relates to the privilege of wearing the White Ensign being confined to the Royal Yacht Squadron, and that they have taken measures that the other yacht clubs may wear such other ensigns only as shall be easily distinguished from that of the Royal Yacht Squadron.” In pursuance of this decision all clubs were notified that the permission to fly the White Ensign was henceforward confined to the members of the Squadron and the matter again appear to be settled.

In notifying these clubs, however, the clerk at the Admiralty being unaware of the secession of the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club from that of England, addressed his letter to the English club only, and in the absence of any instructions to the contrary, the Irish club continued to fly the White Ensign. Matters rested there until a further correspondence between the Admiralty and yacht clubs arose in 1858. Some years previously the Admiralty had issued particular warrants to the owners of particular vessels in addition to the general warrant issued to the clubs as corporate bodies. In that year the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club applied for particular warrants for its members, but was a first refused on the ground, ”that it was defying the Admiralty by flying the ensign, and that the accidental omission of a letter in1842 was not considered to confer a claim to exemption from the general rule then established, viz. the restriction of the privilege of wearing the White Ensign to the Royal Yacht Squadron.” On renewed application, however, the Admiralty weakly gave way and issued particular warrants to members of the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club. This was immediately seized upon by another Irish club, the Royal St George’s, as a grievance. Its Commodore, the Marquess of Conyngham, wrote to the Admiralty to the effect that his club, “felt aggrieved that a club in no way better conducted – the Royal Western of Ireland Yacht Club – should be permitted to carry the White Ensign, as it appears that this privilege is no longer confined to the Royal Yacht Squadron,” and requested permission for the club to again fly the flag. The matter was at length set at rest by the Admiralty in a letter to Lord Wilton as Commodore of the RYS.

Admiralty 25th June 1858

“My Lord, – I am commanded by my Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to acquaint your lordship that my Lords, having received some recent application from yacht clubs for permission to wear the White Ensign of Her Majesty’s fleet, have considered that they may have to choose between the alternative of reverting to the principal established in the year 1842 whereby the privilege was restricted to the Royal Yacht Squadron, or to extend still further the concession which was made in this respect to the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland in the year 1853, and that they have decided on the former alternative. They have accordingly cancelled the warrants authorising the vessels of the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland to wear the White Ensign, and this privilege for the future is to be enjoyed by the Royal Yacht Squadron only.

I am, my Lord, your most obedient servant

H Corry”

Such is the history of the White Ensign in relation to pleasure vessels. The matter was twice before Parliament, once in 1858 when an Irish member found a grievance in the decision of the Admiralty, and in later times in 1883, when Lord (then Mr.) Brassey, replying to Mr. Labouchere for Sir Henry Campbell Bannerman, cited the minute of 1842, and declared that, “as the matter was historical, he was not authorised to make any changes.” Whatever privilege is attached to the wearing of the flag was never sought by the Squadron, and it was not valued by other clubs until the irregularities of many private owners resulted in its use being confined to the old club which had first flown the flag. As a writer of 1858 pointed out, its wearing by the vessels of the Squadron alone eventually gave it a distinction among yacht ensigns, and there would probably have been the same struggle for its possession had the Squadron flown an ensign of purple or pink.

(Transcribed from the original text by John Clementson, May 2019)

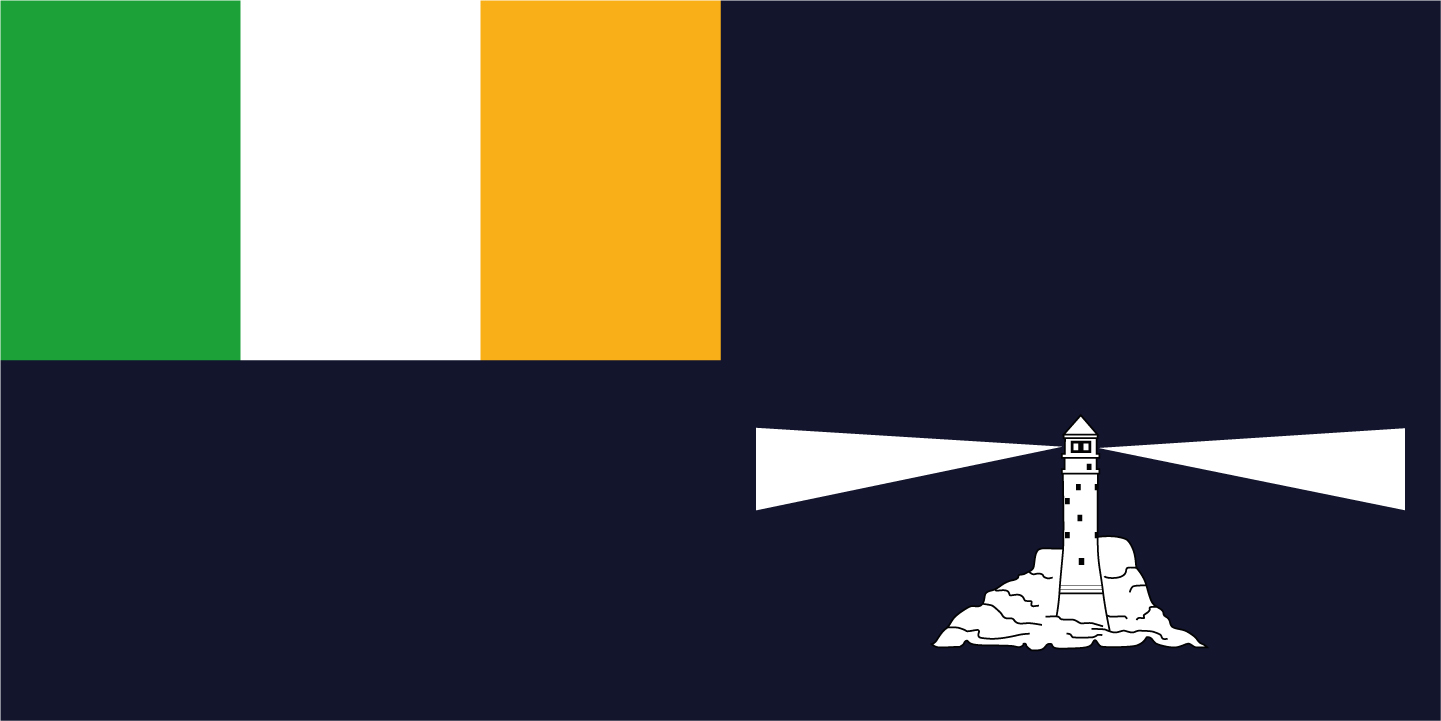

Irish Cruising Club Ensign